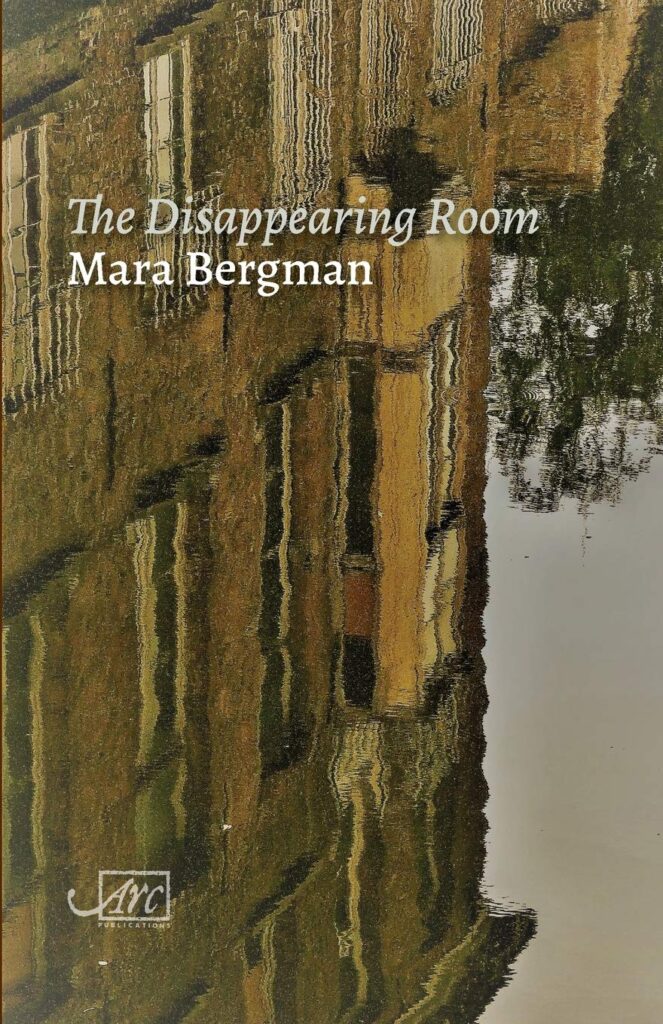

The Disappearing Room

In Mara Bergman’s first full collection, the poet travels from the tenements of New York City to the Sussex countryside, from childhood to motherhood, and beyond. Through a wide range of subjects – steelworkers and young apprentices, photographs and photograms, dolls in a local museum’s hidden collection – she writes with a keen sense of time and place. These are probing poems, seeking to discover; urgent poems that they feel they had to be written. Here are poems about love, loss, friendship, family, fitting in and, ultimately, acceptance. They are infused with joy and wonder, and provide a fresh way of looking at the world.

“Mara Bergman’s poetic voice is a subtle one, the voice of the poems based on the rhythms of ordinary (American-inflected) speech, and has an admirably “natural” or even casual feel that can be deceptive. The developments are hard to predict, the endings open, the writing itself completely free of affectation. There is a genuine search going on here – both poetic and personal. (The scope of her work ranges from intimate pieces about the death of her father when she was a child and studies of the childhood of her own children to larger meditations on displacement and belonging, the plight of the exile, the sense of an extended Jewish family that spans continents and historically inspired pieces about work, a group of poignant social pieces based on old dolls.) Mara’s work captures the vividness of the small detail and makes it resonant, taking it out into the wider world.”

– Susan Wicks

“These are fluent, communicative, unselfconscious poems, yet they display great emotional tact. Mara Bergman knows instinctively what to include and what to leave out. Her poems, with their American inflection, hold a mirror to here and there, to people, places, incidents and to the human heart. Quietly stylish, quietly risk-taking, they show just how much felt life poetry can illuminate: “And the weather of this language is calm, / endless sky.” (“Landscape”). This collection has been a long time in the making and now, to have the poems gathered together, many of them already with the feel of classics, is a delight.”

– Moniza Alvi

“Mara Bergman’s long-awaited poetry book is a model of unflinching gaze and monumental tenderness. Dreamers, workers and artists populate these complex poems permeated by both clarity and mystery. In a New York City tenement, a tailor’s three sons sleep ‘heads side by side on the sofa’ as they ‘rest their throbbing feet on wooden chairs … dreaming their immigrant dreams in thin air.’ In Cheshire, factory girls get ‘a hot dinner every night,/ that’s seven, …’ A woman stands in a river, developing her photographs by holding them ‘under the surface of the water, night/ her darkroom and her lover.’ Bergman’s poetry is elemental, essential.”

– Suzanne Cleary

INVENTORY AT THE APPRENTICE HOUSE

Quarry Bank Mill, Cheshire

Sixty girls in all, ages nine to eighteen, sleeping

in pairs, one room crammed with thirty beds,

not a single fire but a window overlooking the courtyard:

one water pump, three privies with a bucket holding straw.

None would grow past four foot eight; worked twelve

hours in the factory, from six a.m., six days a week,

makes seventy-two, with a break for a dollop of porridge

in the right hand and not a single penny’s wage

except for overtime (their payment guarded by the mistress

in her parlour), but room and board in lieu: a hot dinner

every night – potato and cabbage and twice a week, meat,

eked out with a bit more porridge. The factory may have shut

on Sundays, but church in the morning and church in the evening,

two miles there, two miles back is eight, then an hour

for lessons in the classroom, four long tables, eight long benches,

a sand tray, assortment of slates. Take away nine at least.

And their punishment for leaving? From three to seven days’

confinement and the forfeit of their fortune, often pennies,

sometimes pounds. When found, if a girl couldn’t beg her way

to solitary, her hair was chopped off six inches.

COMING TO ENGLAND

After I unpacked, full of jetlag and timelag and fatigue,

I walked along Lewisham High Street for my very first

cup of English tea, the next day took the tube to Hampstead Heath

to visit Keats. Mornings I woke to the clink of milk,

and once a week the rattling rag-and-bone-man’s cart, at first

not knowing what I was hearing as it made its way down the road

along the park, our slice of country. I spoke of “Lie-ses-ter”

and “Tra-fal-gar”, went to the theatre for 50p and sat

in the heavens, queued up with the others to call home once a week,

used a hand-held shower to save water, pointed to cress

in the refectory and called it clover, laughed at

toad-in-the-hole and spotted dick. Back home at a party

someone had told me you could buy a single cigarette

at an English market, even a match, and that I couldn’t leave

New York City until I’d read Return of the Native.

THE BROKEN DOLL

(early nineteenth-century bisque doll)

Let’s put the baby together.

All the components are ready,

the pale wide forehead and dimpled chin,

a porcelain-perfect skin you want

to smooth your fingers over. Cheeks flushed –

she’s been in the sun, laughing at trees, smiling

at some little girl mum – orange lips

too old for her years, a two-toothed baby smile.

You can just make out her tongue.

Each hair of her eyebrows and lashes

is expertly painted, but let’s fix the eyes,

unlooking, unseeing, rolling like blinds.

Let’s clean out the darkness of lids.

How shall we dress her, this baby doll,

this girl? One fine-stitched dress to cover

her blue-tinged limbs and belly,

a pair of knitted socks and polished shoes

to shelter those curled, chipped toes.

A wide-brimmed hat to protect her.